As Vietnam marks the 80th anniversary of the republic, the higher education system enters a decisive moment. Two recent Politburo decisions—Resolution 68 on strengthening the private sector and Resolution 71 on accelerating educational reform—together define a clear pathway for universities to support national development to 2045. They set expectations for stronger governance, improved institutional capability, deeper industry partnerships and a modernised system aligned with global standards.

Vietnam’s ambition to be among the top 20 education systems globally by 2045 reflects a strategic shift. It is no longer enough for institutions to expand access; they must deliver skills, research and industry value at scale. For university leaders, this is a delivery mandate rooted in national priorities.

1. Resolution 68: A New Role for the Private Sector in Higher Education

Resolution 68 confirms the private sector as a central driver of national growth. It commits to equal access to capital, land, technology, talent and data for private enterprises. For universities, these commitments open several strategic opportunities:

Stronger industry engagement through commercial contracts, service labs and applied research

Spinouts and innovation pipelines that translate academic work into economic value

Flexible short-course offerings co-designed with employers

Governance reforms that allow the inclusion of business leaders on university boards, strengthening market alignment

Resolution 68 positions universities as part of the national productivity ecosystem.

2. Resolution 71: A Framework for Breakthrough Educational Development

Resolution 71 calls for “breakthrough change” in education and links the sector directly to Vietnam’s long-term competitiveness. It emphasises:

adoption of international standards where appropriate

expanded international cooperation

investment in talent development, including improved allowances for teachers

strengthened quality assurance and institutional autonomy

For higher education, Resolution 71 reinforces that autonomy, quality and global alignment are not optional—they are daily operational requirements.

3. A Multi-Stakeholder System: Five Groups, One Framework

Vietnam’s higher education ecosystem involves multiple stakeholders:

Government: human capital productivity, innovation and competitiveness

Universities: autonomy, reputation and financial sustainability

Students and families: mobility, skills and fair access

Employers: job-ready talent and applied research

Donors and investors: transparent governance and predictable outcomes

Resolutions 68 and 71 provide a unified policy foundation, but progress depends on institutions translating these expectations into weekly operational routines.

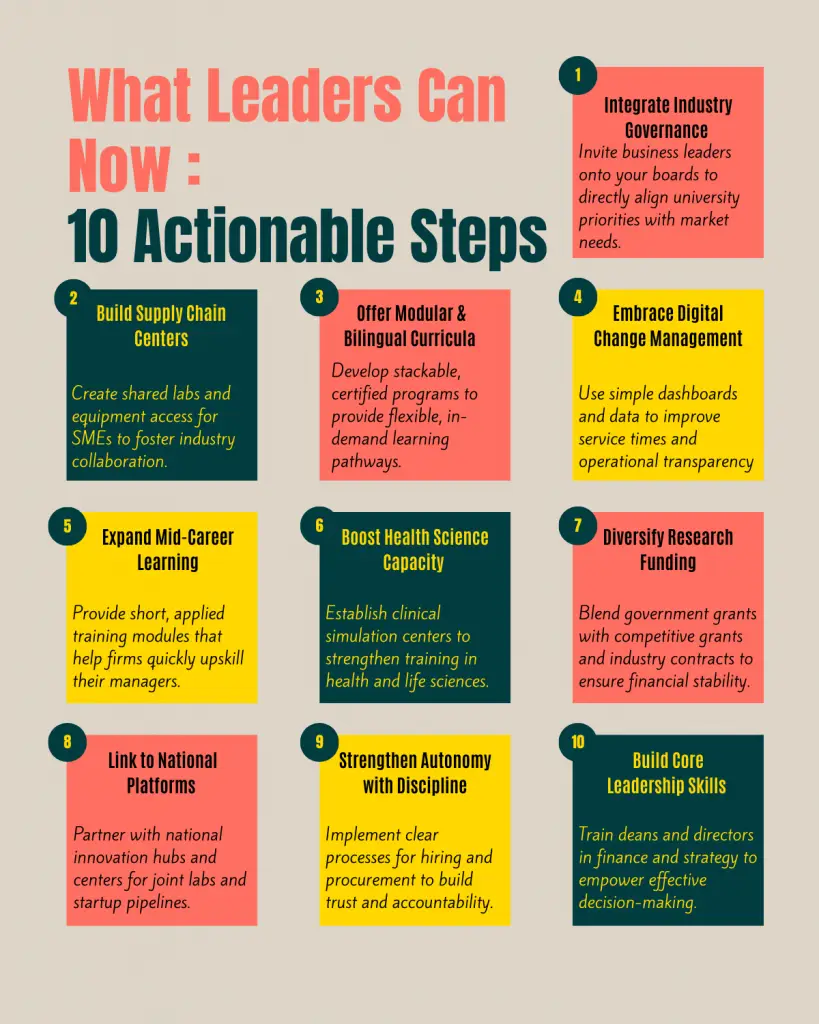

4. Ten Strategic Actions for University Leaders

The following actions align directly with both resolutions and respond to stakeholder needs.

1. Integrate industry into governance

Establish advisory groups and board seats for sector associations and leading firms to strengthen alignment between academic priorities and labour market needs.

2. Build centres that serve supply chains

Locate shared research and training facilities near industrial clusters, such as Saigon High Tech Park. Track measurable outputs including prototypes, firms served and student placements.

3. Design modular, bilingual curricula

Prioritise high-demand fields—STEM, health sciences, business analytics. Offer stackable credentials that accumulate toward full degrees and connect capstone projects to real industry problems.

4. Treat digital transformation as organisational change

Assign process owners, invest in staff training and use dashboards to monitor service delivery, lab utilisation and graduate outcomes.

5. Expand executive and mid-career learning

Partner with chambers and ministries to deliver short, applied programmes. Develop micro-credentials that ladder into postgraduate qualifications.

6. Increase capacity in health and life sciences

Develop simulation centres, strengthen hospital partnerships and expand continuing education for nurses, clinicians and health managers.

7. Use a blended model for research funding

Combine base funding, competitive grants and industry contracts. Publish the funding mix annually to build trust with external partners.

8. Connect with national innovation platforms

Engage with initiatives such as the National Innovation Centre to build startup pipelines, share infrastructure and align institutional KPIs with national initiatives.

9. Strengthen autonomy through disciplined governance

Clarify delegations for hiring, procurement and partnerships. Document decision-making processes and conduct external reviews with industry and international peers.

10. View leadership as core infrastructure

Invest in training for deans and centre heads on risk, finance and portfolio choices. Pair academic leaders with industry mentors and link leadership development to promotion pathways.

5. Managing Risks and Implementation Challenges

Implementing both resolutions will require careful management of common institutional risks:

Procurement delays: Create a specialised unit with standard templates and defined timelines.

Fragmented initiatives: Use a central portfolio board to align projects.

Weak data systems: Start with a small, essential set of metrics and improve quality over time.

Change resistance: Engage staff early and highlight quick wins.

Limited funding: Use joint financing with industry and government to phase investment.

Conclusion: A Window of Opportunity

As Vietnam enters its ninth decade, higher education is framed as a strategic lever for national development. The top-20 goal is documented, the private sector’s role is clearly defined, and education is positioned as a foundation for long-term competitiveness. Resolutions 68 and 71 provide the policy clarity; universities must provide the execution.

Institutions that act early—strengthening governance, modernising curricula, investing in digital capability and forging industry partnerships—will set the standards for excellence and position themselves as preferred collaborators. By building strong leadership, disciplined operations and transparent systems, Vietnam’s universities can contribute decisively to the country’s trajectory toward 2045.